Coding is a major determinant of what dermatologists bill and what they get paid, so it’s critical to keep up with changes to be both compliant and accurate, says Mollie MacCormack, M.D., and Murad Alam, M.D. Demystifying current coding conundrums is even more important as insurers scrutinize the details of your business, they say.

Look for changes in evaluation and management services (E/M) documentation and payment methods within the next two years, says Dr. MacCormack, director of Mohs Surgery/Procedural Dermatology at SolutioNHealth in Southern New Hampshire, and the American Association of Dermatology (AAD) RUC Alternate on the AMA-Specialty Society Relative Value Update Committee (RUC).

Procedure codes are constantly being brought forward for review at the RUC, but coding requirements for office visits haven’t been updated for more than 20 years. The 2019 Medicare Physician Fee Schedule final rule published by the Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services (CMS) in November 2018 included changes designed to streamline documentation requirements, as well as revamp how physicians are reimbursed for providing care.

“While the stated goals of reducing the burden of documentation and better aligning charting requirements with the manner in which medicine is currently practiced are laudable, numerous specialties expressed concern with the proposal as initially outlined,” Dr. MacCormack says.

The AMA has been working diligently on an alternative option, which was presented at the April RUC meeting, she says. The AMA proposal was passed, and it now travels to CMS for consideration.

“CMS could chose to adopt it, modify it or ignore it,” she says. “It is possible that information regarding CMS’s intentions will be included within the next (2020) Medicare Physician Fee Schedule Proposed Rule to be published later this summer.”

DILIGENCE AND CLARITY

While the future of E/M billing and documentation requirements may be

unclear, CMS and other payers consistently pay attention to appropriate

use of modifiers such as 25 and 59 — how they’re being used, reimbursed

and whether instances of overpayment exist, Dr. MacCormack says.

“That being said, the AAD has spent a lot of time on coding education, dermatologists are interested in staying up-to-date on coding issues and I think instances of miscoding are the exception, not the norm,” she says.

Practitioners already know modifier 25 is a significant, separately identifiable E/M service by the same physician on the same day of the procedure or other service, and that it can’t be attached to a procedure code. The challenge is to determine what defines that, Dr. MacCormack says.

“Both payers and CMS worry that the modifier is sometimes used to obtain payment for work that should be considered part of the procedure code,” she says. “Remember that for minor procedures, or those with 0- and 10-day global periods, the evaluation of the lesion to be treated, as well as an effort spent making the decision to perform a procedure is included within the procedure payment. This work cannot be billed for separately using modifier 25.”

ETHICS AND DOCUMENTATION

Maybe you worry about “Big Brother” looking over your shoulder. If you’re practicing ethically, and correctly documenting your

work, don’t worry, she says.

“Even if you are an outlier in how frequently you use modifier 25, if you use it correctly, there is no need to change your practice,” she adds. “The same holds true for being an outlier in other ways, such as level of office visits charged. As long as you are providing appropriate, medically-necessary care — you should bill for what you are doing.”

Approximately 60% of E/M services performed by dermatologists are submitted with modifier 25 attached, compared to about 25% “for the rest of medicine.”

“This attracts attention and also means that changes in modifier 25 payment policy affect dermatology more than other specialties,” she says.

Remember that payers want to reduce healthcare spending, so expect “to see continued attention focused on modifier 25 usage, along with modifier 25 payment policies that are poorly constructed, not grounded in reality, and that may lead to unintended consequences,” Dr. MacCormack says.

“Private insurers are very concerned that if the spending curve doesn’t shift, they could be made irrelevant by new, disruptive healthcare delivery systems,” she says.

STAY CURRENT

Change is inevitable and changes in biopsy coding remain a frequent topic of discussion, says Dr. Alam, professor and vice-chair of dermatology at Northwestern University and an advisor to the American Medical Association (AMA) current procedural terminology (CPT) panel.

Most important to most dermatologists, skin biopsy coding changed this year from one primary code 11100 and one additional +11101, to three primary codes and three additional codes, with primary being shave (tangential) 11102, punch 11104 or incisional 11106, with the add-ons coded as +11103, +11105 and +11107.

“Importantly, if several biopsies of different types are obtained from the same patient at the same visit, only one primary code can be used, and the remaining biopsies of all types are designated by add-on codes,” he says. “This is a deviation from standard CPT practice and important to remember.”

Coding for photodynamic therapy (PDT), for treatment of precancerous lesions using a topical chemical sensitizer followed by exposure to light, changed last year and has become slightly more complex, says Dr. Alam. The older PDT code, 96567, still exists, and should be used when there is no physician involvement in treatment delivery.

However, if the physician applies the photosensitizer and turns on the light, then 96573 is the appropriate code, he says. If the physician, in addition to their role in 96573, also pretreats hypertrophic lesions with curettage or dermabrasion, then 96574 should be used instead.

“The PDT codes especially needed to be changed, because when they were first approved, they were put through in a hurried fashion,” Dr. Alam says. “Physician work time was not incorporated, and as a consequence, the code valuation was much lower than it should have been in many cases. In some cases, it was not accurate to say staff was doing this because the physician was frequently involved in assessing and applying the chemical. Now the original code is still there, but there’s a new code for physician involvement that provides more fair compensation.”

Dr. Alam says that in 2018, two new sets of laser codes

were introduced. These include 0479T and +0480T, which are for

fractional ablative laser fenestration of burn and traumatic scars

for functional improvement. “Wounded warriors, burn victims and others

with contracted scars that restrict motion and impair the activities of

daily living can benefit from the treatments described by these

codes,” he says. “The other new code set, 0491T and +0492T, is

for ablative laser treatment of open wounds intended to speed

and improve healing. In both cases, coding is by surface area

treated, with the add-on code used when larger areas are involved.

So far, both these code sets are Category III codes and, therefore, are

not formally valued by the RUC and not necessarily paid by CMS and most

private insurers. Since insurers can choose to pay

for these codes at levels they deem appropriate, these are called ‘carrier-priced’ codes.”

“A Category III code is an emerging technology code, meaning there’s a new procedure coming out, with not much evidence in support of it, and not that many people doing that procedure yet,” he says. “When data becomes available that confirms more widespread usage, the Category III might be reclassified as Category I, or the type of code that is valued by RUC and generally paid for by CMS and other insurers.”

The process of converting a Category III code to a Category I code includes obtaining Level 1 data, usually a randomized controlled trial to show it works, and developing clinical guidelines to show how a procedure should be done.

“Finally, there has to be widespread use of a code, which doesn’t mean two people doing it hundreds of times each, but perhaps hundreds of people doing it twice a year,” he says. He reminds dermatologists that Category III codes exist for five years and within that time, they have to be made a Category I code or be replaced with another Category III code, “which sometimes happens.”

EQUITABLE SYSTEMS

Although the coding process may seem confusing, on the surface it’s pretty simple, Dr. Alam says.

“Anyone who perceives a code is really important to their business

can submit a code change proposal to modify an existing code or propose a

new code,” he says. “They may choose to hire a consultant and initiate a

code with or without much input from the relevant specialty society —

but they should be aware that the society is there to help them

understand the

process and to offer useful advice.

“There is a common misperception among our corporate colleagues that getting a new code is like winning the lottery, but if the code is not properly designed and worded, it can do more harm than good and actually restrict access by allocating insufficient resources for treatment delivery,” Dr. Alam says.

“And sometimes a new device or procedure can be accommodated successfully within the existing coding framework.”

Underneath it all, Dr. Alam and other advisors say they really want to do the right thing for everyone involved. “We work to come up with a scenario in which dermatology codes are well-described, physicians are compensated fairly and patients can have access to necessary treatments,” he says.

——————————————————

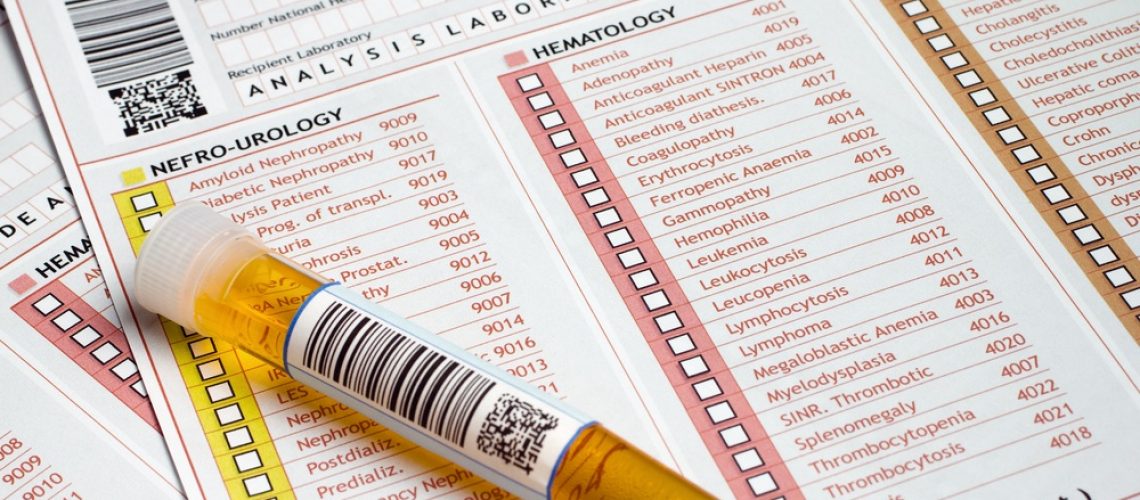

Photo courtesy of: Dermatology Times

Originally Published On: Dermatology Times

Follow Medical Coding Pro on Twitter: www.Twitter.com/CodingPro1

Like Us On Facebook: www.Facebook.com/MedicalCodingPro